When running on multiple processors, Portage uses a simple data distribution algorithm derived from the work of Slattery, Wilson, & Pawlowski[1] and Plimpton, Hendrickson, & Stewart[2].

The following description applies specifically to mesh-mesh remap. Redistribution of source swarms is similar, but must take into account the support of particles (in the form of smoothing lengths) while computing bounding boxes.

For the purposes of this document, distributed remap begins with the call to remap_distributed(...) within the basic driver call of driver.run(distributed). Each processor node has a partition of both the source and target meshes. The spatial extent of the source and target meshes on a given partition need not have any special relationship. Portage uses polytopal intersections of the overlap between source and target cells (or dual cells in the case of nodal remap) to compute interpolated field values. From this point forward we will use the word "cell" to refer to either a cell in cell-based remap or a dual cell in node-based remap.

In order for each target cell to compute interpolated field values it is necessary to know the geometries of all source cells that intersect it. This presents a problem when the source mesh on a partition does not cover the target mesh on that partition. The essence of Portage's data distribution is to bring all source cells that could intersect the target cells on a particular partition onto that target partition. In remap_distributed(...), data distribution is the first nontrivial thing done so that the "search" step has all the data necessary to work correctly. Portage's paradigm of "search, intersect, interpolate" requires that any source cells that could potentially intersect a target cell be available for computation on that target cell's partition. After data distribution, each processor node operates exactly as if it were a serial problem. This is the explanation of Portage's embarrasingly parallel characterization.

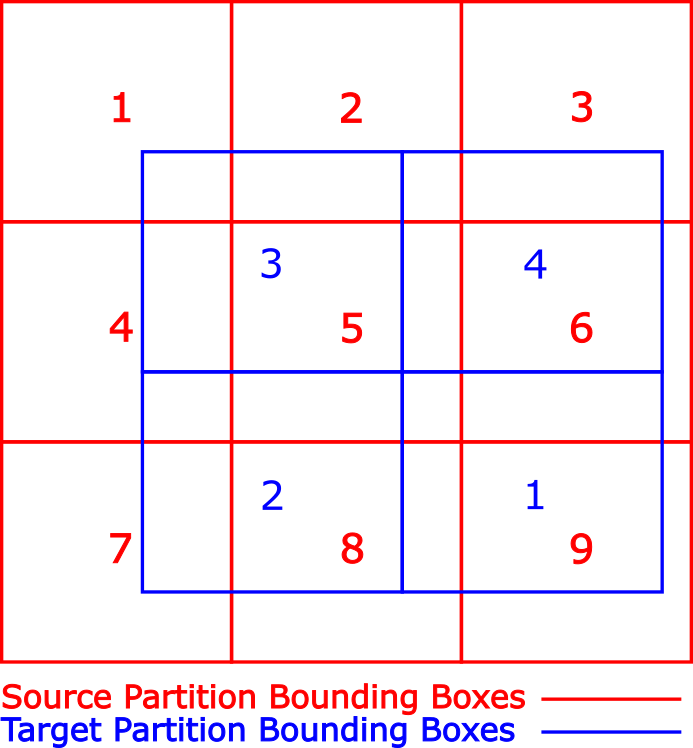

Portage uses a simple algorithm for data distribution. A bounding box is computed for the source and target meshes on each partition. An MPI_Bcast is used to distribute the bounding boxes from all target meshes to each source partition. Bounding box intersections determine the processors to which each processor must send its source partition. In the figure above, the numbered red squares represent the bounding boxes for the partitions of a nominal source mesh. The numbered blue rectangles represent the bounding boxes for the partitions of a nominal target mesh. As seen in the figure, the source and target meshes do not need to coincident. In this remap problem, target partition 1 would receive data from source partitions 5, 6, 8, and 9; target partition 2 would receive data from source partitions 4, 5, 7, and 8, etc.

The same communication topology is used for all subsequent data communication. While sending the entire source partition to a target partition that may need only a few of the source cells is somewhat inefficient, it is easy to implement.

Many pieces of data are sent from souce partition to target partition. For each of these pieces of information, two MPI calls need to be made. The first call establishes the counts of the data that will be sent. The second MPI call does the actual data distribution.

It is worthwhile to note that most data is sent making a distinction between ghost cells and owned cells. Both ghost and owned data are sent in the same request, but the counts are kept separately and the sent data is ordered by owned data first followed by ghost data.

The data distributed for remap includes global ids for all entities, node coordinates, adjacency information within the mesh, and field values, which is potentially multi-material. There are many subtleties in distributing the data. The four most important of which are removing duplicates, converting local references, handling vector data, and field data that is multi-material.

The first subtlety is that because of the way that distribution is handled, namely whole patches are sent, the same cell may be received from multiple ranks. A cell may be owned by only one rank, but may also be a ghost on multiple other ranks. A cell may also only exist as a ghost on any rank. The duplicates are eliminated using the global ids of entities that are sent along with the mesh information. Additionally, if a duplicate entity was owned on any partition that it came from, it is considered owned on this partition.

The second subtlety is that each reference in the adjacency data is represented inherently by local references (local ids). The same global id for each mesh entity (cells, faces, and nodes) can be used to update the references to the new indexing scheme on the partition.

The third subtlety is that MPI data transfer only works with sending vectors of uniform type. So any data transfer needs to conform to this description. In other words, if we need to transfer data that is inherently itself vector data, such as a cell centroid, it must first be "flattened" to a vector of doubles where the individual components of the cell's data are listed in order. Such data must be serialized to the form (e.g. in 2D)

Upon arrival on the target mesh, the data must then be deserialized to the original vector form, still with duplicates removed.

The final subtlety is that multi-material fields greatly complicate data distribution. Multi-material data in Portage is stored in material-centric form, meaning a vector of cells and cell data is kept for each material. Material-centric data is composed of cell indices:

with similarly shaped field values:

Where in the various xij's, the x data corresponds to material i in cell j. Multi-material data greatly complicates the bookkeeping of data distribution because each material acts like it's own mini-mesh. All multi-material fields are assumed to share the same set of material cells. This implies that if a material exists in a cell, all multi-material field values must be known for that material in that cell.

Distributing multi-material field data requires sending, for each partition, the number of materials, the material ids, the number of cells having each material, the cell ids, and finally the data itself. Just as with all other data, since MPI can handle only vectors of uniform type, each of these "ragged right" data structures must be serialized to vectors of common type on the source partition before sending and deserialized from vectors to the ragged right form required by Portage. Finally, multi-material data is inherently more complicated because of its shape but we still need to remove duplicated data and update local ids to the new partition.

[1] Plimpton, Hendrickson, & Stewart. (2004). A parallel rendezvous algorithm for interpolation between multiple grids. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 64(2), 266-276.

[2] Slattery, S., Wilson, P., & Pawlowski, R. (2013). The Data Transfer Kit: A geometric rendezvous-based tool for multiphysics data transfer. International Conference on Mathematics and Computational Methods Applied to Nuclear Science and Engineering, M and C 2013, 2, 1262-1272.